Next: Why did I need Up: Requesting and using resources Previous: Using resources Contents

This section and the next four deal with deeper resource issues in

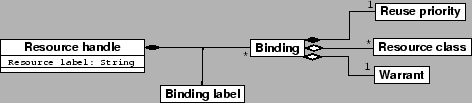

case we want finer grained allocation. See Figure ![[*]](crossref.png) .

However, be warned: this is a complicted area, and almost everything

we need has already been covered. The first-time reader is very strongly

advised to skip all this and go straight to Section

.

However, be warned: this is a complicted area, and almost everything

we need has already been covered. The first-time reader is very strongly

advised to skip all this and go straight to Section ![[*]](crossref.png) .

Go now.

.

Go now.

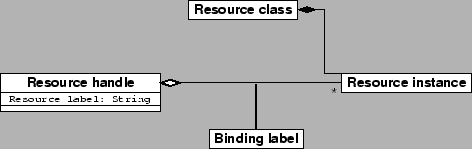

Examples of resource instances are: 1MB of disk space; 10TB of triply-redundant disk space; a socket factory which can generate sockets listening on port 80; a socket factory which can generate sixteen sockets on ports higher than 1023; a socket factory sitting behind a redundant load balancer; a CD-ROM containing the names and phone numbers of everyone in the San Francisco Bay Area. In fact, anything can be a resource.

Each resource class is characterised by two things: resource-specific properties, and what facets it supports.

For example, a file system resource class should support the IFileSystem facet. But beyond that it may have properties such as kilobyte size and redundancy.

On the other hand, a socket factory resource class should support the ISocketFactory facet. But kilobyte size is meaningless to a socket factory. Instead it may have properties describing what port range it supports.

The node's administrator can choose to classify their resource instances how they like. Suppose the administrator has 65535 socket factories, each of which generates a socket on one particular port. There may be one resource class encompassing all these factories, in which case the properties will describe ``a socket factory which can generate one socket''. Or there may be 65535 resource classes, in which case the properties will describe ``a socket factory which can generate one socket on port X'' where X is different for each resource class.

|

![[*]](crossref.png) .

Since there are several bindings within a resource handle we need

to set a binding label for each one to distinguish them. In

our skeleton example we label the disk binding disk and the

socket factory binding net. Beatrix then takes this resource

handle and finds a node with resource instances matching the resource

classes, contracts them and starts the worker.

.

Since there are several bindings within a resource handle we need

to set a binding label for each one to distinguish them. In

our skeleton example we label the disk binding disk and the

socket factory binding net. Beatrix then takes this resource

handle and finds a node with resource instances matching the resource

classes, contracts them and starts the worker.

When the worker netlet starts up it can bind these resource instances

using the same binding labels. Then it can use them. This is the code

in Section ![[*]](crossref.png) above.

above.

For example, if we are running a DNS service then any worker might need a socket factory and some disk space. If a worker died we would want to restart another one. But we would want to prioritise reuse of our old socket factory, because all our clients are expecting us to be listening on that address. We can live without the same disk space, because we can replicate our domain name database from another worker.

Nik Silver 2002-03-09